Is Redemption Possible in Oregon's Capital City?

The Western Edge uncovered a manufactured crisis, backroom deals, political spending, AI slop and a city council bending to appease a police union.

The thing you have to know about Kyle Hedquist — because it’s the thing everyone knows about Kyle Hedquist — is that in November 1994, at age 18, he shot a woman in the back of the head.

Hedquist was a senior at Roseburg High School then. He robbed his aunt’s house, and held a local Pizza Hut employee at gunpoint until he handed over money from the safe.

Then he killed 19-year-old Nikki Thrasher, afraid she would tell the police about his crimes. He left her body on a gravel road in the woods, and later a horseback rider found her.

There was no manhunt, no lies, no trial: Hedquist fessed up to everything and, just short of a year after Thrasher’s killing, was sentenced to life in prison without parole. He would live the rest of his days behind the walls of Oregon State Penitentiary.

Twenty-seven years later, in 2022, Hedquist drew the attention of then-Gov. Kate Brown, who reviewed the ways he’d spent his life in prison: volunteering with prisoners in hospice, mentoring other inmates on how to write a resume, taking seminary classes and speaking to at-risk students at Roseburg High School about where his life had gone wrong. At 45, Brown granted him clemency.1

“Mr. Hedquist,” Brown wrote in a report to lawmakers on her decision, “engaged in rehabilitative programming on a level rarely seen by other adults in custody, proactively prepared himself for re-entry into the community … His continued incarceration does not serve the best interests of the State of Oregon.”

When Hedquist walked out of prison, everyone knew he was a murderer. Newspapers and TV stations ran stories about his clemency. Thrasher’s mother told a television station she was unaware he’d been released. Politicians slammed Brown, even some in her own party, for taking mercy on a killer.

Eventually, the headlines died down. Years passed. Hedquist got a job. He got married. He spent his free time volunteering with the elderly, picking up trash around Salem and signing up for community boards.

It felt like Oregon’s capital city opened its arms to him.

In 2024, Salem’s city council unanimously appointed Hedquist to a spot on the Community Police Review Board, or CPRB, a volunteer citizen panel that reviews complaints about police brought by residents. In early December 2025, city leaders reappointed him to the board for another term.

But days later, something changed.

The city’s embrace of Hedquist abruptly ended.

“The death of Nikki Thrasher is the gravity that pulls at everything I do. I ended her life and I am forced to live with the agonizing math of that reality: I can never give enough, serve enough or do enough to equal the life that I took.” — Kyle Hedquist

On Dec. 18, thousands of citizens across Salem received a text message. It looked like an emergency alert. “Action needed!! Your Salem city councilor created a mess by putting a convicted aggravated murderer on Salem’s Community Police Review Board. The council had no vetting process, then reaffirmed the same murderer a second time even after they learned his background,” it read.

The message, paid for by the local police and fire unions, urged citizens to pressure their city councilors to revoke Hedquist’s new term, and boot him from the police board.

Weeks later, on Jan. 7, Hedquist — bald, with glasses — wore a gray suit jacket and purple tie as he stood at the microphone in front of the Salem City Council. He had just 3 minutes to speak.

“I stand here a member in good standing, checked every box, met every requirement, fulfilled every voluntary duty. Yet, mysteriously, I became the ghost in your machine,” he said, choking up, his voice strained and rising.

“For 11,364 days, I have carried the weight of the worst decision of my life,” he said. “There is not a day that has gone by in my life that I have not thought about the actions that brought me to prison. I replay the details. I search for a way back to my own humanity through the wreckage of that singular moment. The death of Nikki Thrasher is the gravity that pulls at everything I do. I ended her life and I am forced to live with the agonizing math of that reality: I can never give enough, serve enough or do enough to equal the life that I took. That debt is unpayable.”

A long line of Salem residents waited to say what they thought of Hedquist, his guilt, his innocence, the quality of his character. There were people he knew, people he didn’t. It was less a council meeting than a public trial.

“A man that takes a life, his life shall be taken,” said one man in an American flag shirt with a cross. A woman wearing a shirt that said PSALMS 118:6 - “The LORD is on my side” - shook her head in contempt at the councilors.2

“AIC Hedquist should not be here crying, and he should not be here screaming,” said Elizabeth Infante, who served alongside Hedquist on the board in 2024. “If I was him … I would have came out to the community, gone into the woods and lived my life out.”

Several people voiced their support of Hedquist. “If someone has paid their debt to society and spent decades living differently, when do we allow them back into full participation?” one woman asked. “If the answer is never, then we are closing a door that even God does not close.”

The city councilors who had in the past embraced Hedquist’s volunteerism appeared aghast at his extremely well-known record and listened silently as the community excoriated him. That night the council voted to remove him from the CPRB.

What wasn’t made clear to the public was that this was a manufactured crisis. A Western Edge investigation found that as Salem squabbled about Hedquist, closed-door deals were being made and a bare-knuckled pressure campaign was being waged by the local police union to influence officer oversight.

When the Salem Police union triggered this crisis, the darkest parts of the city rose to the surface. People made racist remarks and sent death threats to council members. A news outlet created an AI slop video about Hedquist that spread on social media. People wrote in comment sections that he deserved to be murdered.

“I think people struggle with redemption and mercy and justice,” Hedquist said in an interview. “I spent 28 years in prison. Maybe that’s not enough in your eyes.”

Scotty Nowning sees the worst side of humanity in his job at the Salem Police Department. As a detective in the special victim’s unit for the past decade, he investigates child sex abuse, rape and sexual assault. It’s a job that’s taught him a lesson on how to do his other job as union president for Salem’s rank-and-file officers: “Not getting too emotionally attached to people’s tough situations,” he said in an interview over coffee in late January.

Like Hedquist, Nowning is bald, and wears glasses and suits. “In 1994, he killed Nicki Thrasher. In 1994, I went to the police academy in Tucson, Arizona,” he said. “Every day since, I was a police officer.”

Nowning has a problem with a murderer being trusted with any oversight over the police. From his perspective, the CPRB is in a position to make judgements on how local police do their jobs. “He pops out of prison and within a year, he’s going to be like, ‘I’m going to go ahead and judge you on how you’re doing that job.’ And I’m like, ‘Based on what?’ Based on what life experience?”

The CPRB — comprised of seven citizens — functions in an entirely advisory role to the Salem police. If city residents lodge complaints against police officers, but are unsatisfied after internal investigations, they can then bring their complaint to the CPRB. The board, which did not meet at all in 2025, reviews the complaint and offers suggestions to the police. The police can take or leave what they say: If the chief decides his officers do not need discipline, the citizen board has no recourse.

This modicum of oversight only exists because the community demanded it 30 years ago.

In the summer of 1996, 63-year-old Salvador Hernandez was in his kitchen when Salem police officers burst through the front door of his home and shot him to death. They were searching for someone they believed was trafficking heroin across the U.S.-Mexico border. After the shooting, the involved officers portrayed the elderly farmworker as a potential killer who lunged at them with a knife; his family members who were in the home at the time said Hernandez was only making breakfast. An all-white grand jury in Salem quickly cleared the officers.

People were outraged, and protesters gathered at Willamette University with banners demanding to “hold police accountable.” After five years of contentious debate over what police oversight should look like, in 2001, the board formed. According to newspaper reports, the police union president at that time derisively called the CPRB “an attempt to appease the minority community.”

“Should we be training this person on police tactics? Should we be having him ride in police cars with police officers and saying, ‘Hey, this is how they do what they do?’” — Scotty Nowning

Applying to volunteer on the board is simple: people fill out an application, and, if appointed, go on a ride along with police. In 2024, Hedquist completed those steps, noting on his application that he had 28 years of experience with the justice system and served as president of the “Lifer’s Club,” a prisoner-led group to help people with life sentences overcome despair.

He was voted onto the CPRB with little fanfare. The council made no comment on his past crimes, no mention of the headlines lambasting Gov. Brown for releasing him, no discussion of a sprawling profile about Hedquist’s consulting work with lawmakers in the Oregon State Capitol that ran in The Oregonian.

Signs emerged last summer that the city’s feelings about Hedquist were shifting. At a meeting that drew almost no attention, some city council members deliberated if CPRB members should also undergo a criminal background check. By fall, Hedquist — whose term would expire in early 2026 — agreed to what he was told was a routine check. He failed it.3

That’s when Scotty Nowning heard about Hedquist, which “raised the red flag.”

At first, Nowning described practical concerns: He didn’t want a convicted murderer learning how police do their jobs. “Should we be training this person on police tactics? Should we be having him ride in police cars with police officers and saying, ‘Hey, this is how they do what they do?’” he said. Nowning reached out to a city human resources director, who assured him CPRB members learned no tactics, that all training materials given to members are public information and that Hedquist had never received “confidential information” during the year-plus he’d already served on the board.

Then, Nowning’s concerns became more philosophical: Should all citizens — even ones who have committed murder — have a say in police oversight?

Three decades after Salem residents demanded citizen oversight, Nowning sought to influence which residents could get that power. “Just because someone hired him and he’s over at the Capitol dressing nice and whatever, it doesn’t really mean anything,” he said.

He believed that when Salem’s city councilors learned of Hedquist’s criminal background, they, too, would agree he didn’t belong on CPRB.

“I literally thought once we found this out, it was going to be a 9-0 vote,” he said.

It was not.

In December, city councilors voted 5-4 to keep Hedquist on the board, and to also allow him to serve on other city boards.

Nowning and his unionized officers were enraged. They wanted Hedquist gone, and top police brass did as well, according to emails.

Nowning quickly sent off a letter to city council, but he didn’t stop there. He hired Rushlight Agency, a marketing firm, to create a plan of attack. Nowning and the head of the Salem firefighters union, Matt Brozovich, then dumped a combined $8,750 into a media blitz to pressure the city council to change their minds about Hedquist.4

When the text message vibrated thousands of phones across Salem, it included a link to a website.

Hedquist and his wife, Kate Strathdee, were sitting on the couch watching TV when Strathdee’s phone buzzed. It was a text from a friend: “Are you guys OK?” it read, and linked to the website.

Like people across the city, they clicked. There was Hedquist’s face, the words cold-blooded killer.

The website warned that Hedquist’s volunteer roles with the city gave him the power to hire, promote and fire unionized public safety employees.5 People needed to act, and give the city council a piece of their mind.

People wrote to city leaders. Some defended Hedquist, saying he needed a second chance. Most included some version of the phrase, “I believe in second chances. However...”

Two people who knew Thrasher in high school and now live in Salem opposed him being on the board.

“He has been given a second chance that Nikki Thrasher will never be given. I do believe that allowing Mr. Hedquist to serve in any position of power or oversight would be disrespectful to Nikki Thrasher’s memory, her family, and our community,” one wrote.

Others who had no connection to Thrasher teemed with righteous anger.

“You pieces of human shit having a FUCKING MURDERER who executed a 19 year old girl on the Oversight board are EVIL … Hope you all get cancer and suffer then burn in Hell, like your scumbag buddy murderer,” one constituent wrote.

Tabloid headlines weren’t far behind: The New York Post, Fox News, The Gateway Pundit. The Daily Mail yelled: “Woke Oregon city hires MURDERER who executed teenage girl to its police review board.”

By Christmas morning, Hedquist and Strathdee were receiving death threats. They started to look over their shoulders wherever they went.

Then came the AI slop video.

The owner of the Salem Business Journal is named Jesse Peone. He has an MBA, an economics degree and touts his “experience with ligislation” (sic) on his website’s biography page. On Dec. 30, he posted a video to Instagram and Facebook.

“A convicted murderer was just appointed to the police review board,” Peone said into a tiny microphone.

Unlike ethical crime journalism, which would require a review of public records and interviews to learn the context around Hedquist’s crime, Peone narrated over a series of AI-generated images reenacting Nikki Thrasher’s killing, inventing whole scenes to shock his audience.

The Salem Business Journal’s AI slop video shows Hedquist as a bearded adult man; Hedquist was 18 in 1994. In the video, Thrasher is depicted as a smiling young, blond white woman dressed in a sunny, yellow 1950s housedress with a Peter Pan collar, then lying dead in a muddy ditch. In fact, Thrasher was Korean-American.

“I believe in forgiveness and in second chances, in a lot of cases,” Peone said at the end of the video. “This is not one of them.”

Hedquist felt like he was under a microscope. “People do recognize me in public now, they will call me out,” he said. “People will holler my name out in parking lots. It’s like, ‘Oh, OK. Let’s just get to the car.’”

As his uneasiness grew, and as citizens squabbled, Salem’s two city councilors of color — Mai Vang and Irvin Brown — reported receiving death threats over their votes of support for Hedquist. Slurs trickled into their DMs on social media. Angry people called some councilors’ day jobs, demanding they be fired.

Behind the scenes, money flowed from the police and fire unions to city council members who backed them.

The Salem Police Employees Union, led by Nowning, gave $1,500 to Mayor Julie Hoy’s re-election campaign in early December, according to campaign finance records. In January, just after the council removed Hedquist, the firefighters union sent another $5,000 to Hoy and $2,500 to Councilor Deanna Gwyn. Brozovich, the head of the firefighters union, denied the campaign contributions had anything to do with removing Hedquist. Hoy did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Gwyn did not respond to an email requesting comment.

Councilors who had previously supported Hedquist being on the CPRB began to have second thoughts, too. Within days of the text messages, city councilors capitulated to the police union demands, according to emails obtained through public records requests.

In an email sent the day after Christmas to the fire and police union presidents, Councilor Vanessa Nordyke — who is challenging Hoy in this year’s mayor’s race — said: “This vote was a big mistake on my part.” She requested the men keep the contents of her email a secret from Hoy and the other councilors, appearing concerned about collusion and public meetings law. She then asked if they approved of her proposed changes to the police oversight board. Those included mandatory background checks for the board, banning some people with misdemeanors and making a police ride along the first step in even applying to the CPRB.

Nowning said the council went above and beyond to satisfy him. “They probably fixed it more than I was even asking.”

As Nordyke was bowing to union pressure, and Hoy was accepting donations, Councilors Mai Vang and Irvin Brown stuck to their belief that Hedquist deserved a second chance.

“It’s not as if he was hiding this, pulling a fast one,” Vang said in an interview. “A healthy community should be able to integrate (formerly incarcerated people) into being a positive member of the community. That was my thinking.”

“I just find it funny, Madam Mayor, that we want to not have someone with a felony serve when we have a commander-in-chief who has 34.”

— Councillor Irvin Brown

In exchange for that belief, Vang saw waves of threats and slurs come into her re-election campaign and social media accounts. It was only at that point she realized the larger campaign against Hedquist, and anyone who supported him, was underway.

When he spoke at the January public meeting to remove Hedquist, Brown would point out the farce unfolding at city hall as he saw it.

“So just for clarity, I want to say out loud what some folks may be thinking,” he said. “We want to discredit someone from serving or volunteering because they are a felon.”

“I just find it funny, Madam Mayor, that we want to not have someone with a felony serve when we have a commander-in-chief who has 34.”

“Thank you, Councilor Brown,” Hoy said abruptly.

In prison, Hedquist became a volunteer. Inside the walls of Oregon State Penitentiary, he spent time cleaning and feeding prisoners in hospice.6

One year, he successfully lobbied prison leaders to build a playground for children to make the visitors area more welcoming to families. He has no children of his own, but he could see how building something like this would improve everyone’s life: People realized if they stayed on their best behavior, they would get to see their kids during visits, watch them play on that playground.

“It impacts a lot,” Hedquist said. “Now people are like, ‘oh, cool, when’s the next family event? …Like, ‘I want to see my kids next month. I’m not going to fight that dude. I’m not going to yell at that guard.’”

After the playground went up, Hedquist felt inspired to do more. “It was a feeling that this could be a life inside,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be just misery.”

He founded a Toastmasters club, facilitated work training and resume writing classes and assisted Black inmate groups organizing culturally specific events.

All of it would eventually factor into his release.

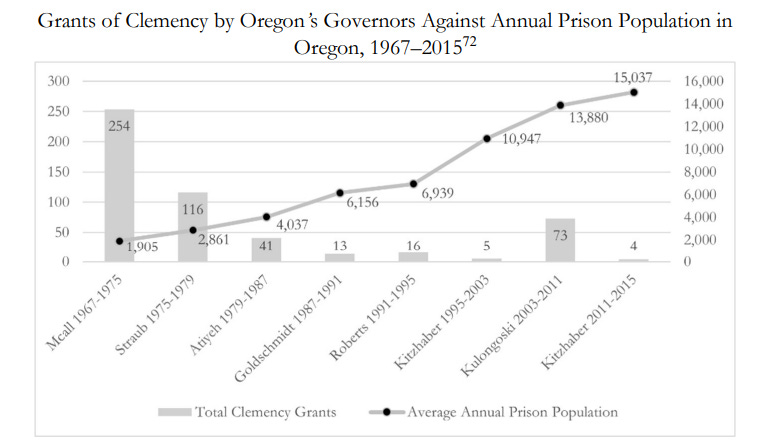

When Hedquist received clemency from Gov. Brown in 2022, it was hardly unprecedented. Since Oregon’s constitution was written in 1857, the governor has always had pardon power. Even in the state’s earliest years, people convicted of brutal crimes were given second chances. Gov. Sylvester Pennoyer, who served from 1887 to 1895, pardoned 18 people who had been convicted of murder, attempted murder and manslaughter.

For much of America’s history, executive leaders nationwide viewed the justice system as a two-way street. Presidents since the United States’ founding regularly used clemency powers, issuing more than 10,000 remediations in sentences between 1885 and 1930, according to a 2019 law review by Lewis & Clark law professor Aliza Kaplan and attorney Venetia Mayhew, who worked directly on Hedquist’s clemency case.7

While there has never been a concerted effort to curb the Oregon governor’s singular pardon power, over time state governors became increasingly reluctant to use it.

Kaplan and Mayhew argue that police and prosecutors leveraged rising crime rates to gain a type of political power they had not had in previous decades. If a governor felt an urge to use their clemency powers to address an injustice - the death penalty, racial disparities, youth incarceration - law enforcement might label that governor as “weak on crime” and extract a political cost by drumming up public safety fears.

Brown, in her last years as governor, bucked that threat when she released thousands of people from Oregon’s prisons in the worst years of the COVID-19 pandemic – including Hedquist.8 The former governor declined to comment for this story.

“Gov. Brown did a lot of clemency in comparison to every governor before her in Oregon,” Kaplan said. “In the end, more than any governor in the history of governors.”

Kaplan describes Hedquist’s case as a “turning point” in clemency in Oregon. To her, the scale of effort to remove a single man from a largely toothless oversight board makes sense as a part of the continued backlash to the sweeping clemency effort.

Gov. Brown’s decision to allow formerly incarcerated people to return to society, and in Hedquist’s case to participate in public life, has stuck in the craw of the Marion County district attorney and local law enforcement. Salem seemed to be sending a message that formerly incarcerated people have no place there.

But the city has always been a prison town. Historical records show that since the first walls of the state penitentiary went up in 1866, Oregon’s capital was built by people who had been locked up for crimes. Prisoners harvested the bounty of the Willamette Valley, producing flax for textiles and running a dairy that put milk in the bellies of Salem’s school children. Inmates cut lumber from surrounding forests. They poured molten metal in the prison’s foundry to make wood furnaces that warmed local homes, and made the very bricks that built Salem’s city hall.

In the flurry of media around Hedquist’s clemency, and then his re-appointment to the police review board, local District Attorney Paige Clarkson went to the news. During this latest round of press, she told KOIN News she, too, believes people can change, but insisted a line must be drawn for victim families.9 “We wouldn’t put a bank robber as the president of another bank,” she said. “We wouldn’t give a child molester the ability to run a daycare.”

Hedquist was neither trying to run a bank, nor a daycare. He was trying to volunteer.

All of his volunteer work with seniors, the homeless shelters and his roles on both the fire and police boards halted because of the public backlash.

In prison, he believed that if he was ever given another chance to be a free man, he would carry the lessons he learned in prison out into the world. He would be a better person. But the message he received from Salem seemed to be the opposite. “It’s very conflicting,” he said. “It’s like, do you want more of that or less of that? Because you’re sending me some wrong messages here.”

By the time Salem’s City Council met Jan. 7 to reconsider Hedquist’s seat on the board, the majority of councilors had already made up their minds to get rid of him, according to emails reviewed by The Western Edge. In fact, so many conversations had happened behind closed doors that one councilor walked out of the meeting before it started, fearing city leaders had violated public meeting or ethics laws.10

“In my opinion, tonight’s meeting has become a circus because of behind the scenes discussions and input from people who want to make it a spectacle so they can get into the news under a false narrative,” Micki Varney said before she strolled out. (Varney did not respond to multiple emailed requests for comment.)

By the end of the meeting, all but two councilors — Brown and Vang — decided to strip Hedquist from his CPRB and fire board positions and put rules in place that would ban him, or anyone with certain felonies on their record, from being on a public safety board. Councilor Deanna Gwyn performatively held up a photo of Thrasher, and read from an anonymous letter supposedly sent to the council by a friend of Thrasher.11

In the end, Hedquist lost everything: his position volunteering at a Salem homeless shelter, his volunteer position helping at the city’s senior center, his job advocating for criminal justice reforms at the state Capitol. (When reached for comment, his employer described his lay off as coincidental and unrelated to the controversy.)

“People who are convicted of crimes, it never ends,” Kaplan, the law professor, said reflecting on Salem’s police board drama. “Society’s judgement. Whether Kyle spent 28 years or 40 years, it would never end.”

Hedquist thinks that when he left prison, he tried to be the most honest person he could be. He knows murderers who served their sentences and quickly changed their names because of fear that society would never accept them. He wonders if he should have done that, too.

Still, he did not expect to be chewed up by a city he had spent his post-prison life trying to make cleaner and safer through volunteering. Without all the civic activities to fill his day, Hedquist found comfort tinkering with the lights in tiny holiday displays at home. He had no control over the light switches in prison, and proudly showed off a particularly hard to wire display of miniature ice skaters to a reporter.

“It’s just this weird back and forth. Like, we want to be progressive. We want to be a city of second chances, but just not for everyone,” Hedquist said. “I felt bad for the city. … What people in authority were saying just wasn’t true.”

He likened the drama to “backdoor conversations” he saw frequently in prison when rival factions would make plays for control of the yard.

“I know (Scotty Nowning’s) an officer, but in my eyes I saw him as a gang leader and he was posturing with another gang, the Salem City Council,” he said. “And this gang is dominant now. The way it would work in prison is once that happens, that dominant gang is in charge.”

He felt caught in the middle of a turf war the police union won.

Where Hedquist would once chat with his neighbors after he mowed their lawns, he now finds closed doors. Where he once viewed the Salem police as reliable friends he could call if he saw a person in mental health crisis, he now worries officers are following him.

He and his wife, Kate Strathdee, have considered moving out of Salem, fearing further retribution.

Strathdee believes the public campaign against Hedquist had very little to do with the police review board itself. In her mind, the police union flexed its power within the city and elected officials sacrificed her husband because it is a contentious political season.

Meanwhile, she wonders what was gained for Salem, the prison town where people leave incarceration every day.

“Kyle is like the best of the best of people who have come out of incarceration,” she said. “If they deny him a position of volunteerism, what does that tell everyone else who is trying to recover?

“It says if he’s not good enough, no one will ever be good enough,” she said.

In a letter to Oregon’s legislature, Gov. Kate Brown wrote the following: “For crimes committed at the age of 18, Mr. Hedquist was convicted of Aggravated Murder on November 17, 1995, and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole and ordered to pay fees and assessments. Since his incarceration, Mr. Hedquist demonstrated excellent progress and extraordinary evidence of rehabilitation. Mr. Hedquist is the person responsible for bringing Toastmasters to prisons across the country and he volunteered in the hospice program for 20 years where he cared for people as they died without family around them, volunteered for years in the disciplinary segregation unit, pursued higher education, mentored men, was deeply involved in religious programming, and secured a job prior to his release. Mr. Hedquist expressed sincere remorse for his actions and took time to address the issues underlying his convictions. He engaged in rehabilitative programming on a level rarely seen by other adults in custody, proactively prepared himself for re-entry into the community, and crafted a solid release plan with community support, including living with a retired DOC Chaplain and parole officer. The Douglas County District Attorney’s office did not provide victim input to the Governor’s office, which I considered in making my determination. I concluded that Mr. Hedquist demonstrated excellent progress and extraordinary evidence of rehabilitation and that his continued incarceration does not serve the best interests of the State of Oregon.”

The woman in the Psalms T-shirt, Betsy Vega, did not disclose that she is currently running for city council against Mai Vang, a councilor who defended Hedquist’s appointment to the CPRB. The Salem police union president told The Western Edge his organization plans to endorse Vega.

When Hedquist was released, his criminal record was not expunged.

Campaign finance records show the attack website and text messages were paid for by Salem Fire PAC. Salem's police union does not operate a political action committee. In emails

As a member of the Civil Service Commission, which had been dormant in Salem for years, Hedquist would have had input on certain standards for promotion within the fire department, according to Salem fire union president Matt Brozovich.

Oregon has one of the oldest prison populations in the country due in part to its lengthy mandatory minimum sentences under Measure 11, which voters approved just weeks before Hedquist murdered Nikki Thrasher.

Most recently in the Northwest, President Trump used his pardon powers to clear convictions and charges against notorious Washington state Proud Boy organizer Ethan Nordean for his role in the attack of the United States Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Nordean had been sentenced to 18 years in prison for seditious conspiracy, one of the most severe penalties to come out of the insurrection. Trump also pardoned Oregon's David Medina, who is now running for governor after smashing a House speaker sign in the U.S. Capitol and chummily associating with the "Camp Auschwitz" T-shirt guy that day.

A 2024 review of Governor Kate Brown's use of clemency by Kaplan and another Lewis & Clark law professor, Mark Cebert, posits that Browns' actions may have been the most significant use of clemency by any governor in the previous decade.

A 2023 report to the state legislature on clemency indicates that Douglas County District Attorney Rick Wesenberg's office failed to provide any victim impact statements as Gov. Brown considered Hedquist's clemency petition. Wesenberg would later complain in the media that Brown's decision on Hedquist hurt crime victims. Wesenberg did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Salem city councilors conceded in 2025 that they broke public meetings laws by making decisions outside the public view regarding the employment of a former city manager, according to the Salem Reporter. When she walked out of the Jan. 7 meeting about Hedquist, Councilor Micki Varney said she was worried about more potential violations because “too often we’ve been getting the cake after it’s baked.”

The anonymous emailer only identified themselves as “KS.” Emails obtained by The Western Edge show the person responded several times with city councilors supportive of removing Hedquist. Requests for comment sent to the anonymous email were not returned.

I’ve very much been hoping for a deeper dive on this issue—thank you so much for this

Thanks for this story. I would love for you to pick up the story of the first black judge on the Marion county circuit court, Erious Johnson, being driven out by Amy Queen. Both Queen and the Salem prosecutor were hostile to Johnson and married to Oregon police officers. As I recall the police union donated to her campaign. I think it is important that people know that Marion county, the seat of Oregon government, has a sundown court.